Treatment, letter of intent and movie pitch: the ultimate guide.

Introduction.

Your film script, or that of your author's, is ready to be sent to a commissioning panel (such as BFI Film Fund, Eurimages, MEDIA Sub-program). However, you still need to put together your full application, which includes treatment, synopsis (when necessary), statement of intent, pitch (when possible), and you have no clear idea of how to make a great, well-written, and convincing proposal.

How then do you write a synopsis, a statement of intent, or a pitch? What is the difference between a synopsis and a treatment? Providing answers to these questions is the ultimate goal of this guide which covers the following:

Definition of a synopsis, treatment, pitch, and statement of intent,

Writing tips,

A checklist of everything that should be included in your proposal.

Who is this guide for?

Based on my ten years’ experience as a script consultant, these recommendations are for anyone who is:

A screenwriter looking for writing tips,

A producer/distributor/agent looking for advice to unveil their projects or to help their writers.

Whatever your background or place of origin, this guide–although written in English by a Frenchwoman, is made for you. Over my ten-year career, I have read hundreds of scripts and treatments in French, English, and Spanish. And, I’ve come to the conclusion that no matter the slight cultural differences in terminology or content from country to country, the tips in this guide remains relevant regardless of which part of the world you are applying to.

Timetable

Want to go straight to the part you are interested in? Simply click below:

Disclaimer: Before reading this, please note that the tips compiled in this guide, although intended to help, do not guarantee your project’s success after scrutiny of a commissioning panel. It's the reviewing panel who ultimately decides this.

⚠️The article is also available in PDF format. To download it, just click here.

Treatment and synopsis.

1) The difference between synopsis and treatment:

Before going further, it is important to understand that the definition of treatment is different from country to country and even from one organization to another. Before submitting an application, whatever your location is, it is your duty to check the suitable terminology for the country you are applying to. The difference in definitions between French and English-speaking countries can be quite confusing.

In France, the synopsis for us means “treatment” which, in both French and English, pertains to a story’s detailed summary written in prose. For a feature film, it's typically 15-20 pages long; whereas in English-speaking countries, a synopsis is a succinct summary, not longer than one page, designed to quickly convince producers.

You see, the difference between these two definitions is huge and can be to your disadvantage if you are not mindful. Please note that differences may also exist from one organization to another, making it important to verify first.

2) A few film funding programs:

Let's have a look at some of the film agencies present in Canada and Great Britain where you can submit your projects.

In the United Kingdom:

→ The MEDIA sub-program of Creative Europe

→ Creative Scotland Film and Television Funding Program

→ Northern Ireland Screen Fund

In Canada :

→ Bell Broadcast and New Media Fund

→ Nova Scotia Independent Production Fund

This is obviously a non-exhaustive list, so if you know of any other film funding programs, feel free to contact me so I can add them to the roster.

3) Why do we need a treatment at all?

The goal of a film or television treatment is to convince the reader–whether it's a producer, distributor, or member of a commissioning panel, and to make your work engaging and appealing. Consider your synopsis as a marketing tool, which must not only be convincing, but should also demonstrate your project’s coherence, how the film resonates with its time, and your author’s ability in developing a project. Apparently, all these points are important, but the story’s coherence is, indeed, the most crucial. What this means is:

→ If the treatment is well written and coherent, the reader will want to read the rest of the material.

→ If the treatment is poorly written and filled with inconsistencies, the reader will not want to read the rest of the material.

We cannot emphasize enough the importance of defining and constructing the treatment well–as this serves as your visit card. You must therefore spend ample time in putting together a high-quality treatment.

4) What are the elements to include in your treatment?

Although treatment writing allows you the freedom and limitless creativity in style and form, it is expected of you to include the following few key elements :

a) The tale.

The treatment is the film’s summary and must, therefore by its definition, summarize the story and its structure–from the most to the least important parts of the plot.

!! A QUICK REMINDER:

Keep in mind that “the main plot” usually concerns the hero or the heroes’ journey.

This is the plot that justifies the film's existence and essentially the one that takes up most of the film’s storyline.

The secondary plot, also known as “subplot”, can cover less important aspects of the hero’s life (e.g. their love life, if it is not part of the main plot) or themes involving secondary characters.

So far, we've covered general concepts, but the elements that should be found in the synopsis in a more technical and detailed way are as follows:

The setup - the description of the hero’s life at the beginning of the film as in “everything was great until…”

The complication - this is what makes the hero’s life difficult,

The main dramatic issue or issues - the issues that the plot brings up which will intrigue the viewer and engage their curiosity throughout the film,

The main plot's twists - this allows the main plot and subplot to change (there's no need to know all of the film’s details, but to understand the plot better, we need to know some of the main twists),

The "all is lost" moment - the time when the hero’s goals seem unachievable,

The climaxes that punctuate the story and the final climax.

The resolution - how the story ends, the denouement/culmination. If the story is split into acts, you must explain each of their endings (which are usually the most important parts of the story)

b) The theme.

Similarly, the topic and themes mentioned in the film must be clearly explained in the treatment. If we do not understand what the film is about, then the treatment is of no value. Every film speaks about a specific topic or multiple ones. It is the author’s job to find a way to clearly communicate the film’s topic in the treatment–even in the synopsis.

c) The characters.

A strong concept and a bunch of good ideas are not enough to create a story that will meet the viewer’s expectations.

For a story to resonate with the general public, you need much more than plot twists –you need something human. In other words, you need to foster a connection between the viewer and the characters–whether it is a good or bad one.

Even in the early parts of the treatment, your characters must come to life, become vivid, and the viewers must be able to relate to them one way or another.

🖊How to achieve that?

The personality and physical traits. To facilitate the identification process, the general public, or reader, must know the characters–not only physically, but psychologically as well. As the writer of the story, your job is to describe their physical traits, their behaviors, their assets, as well as their flaws. Put differently, the audience must be able to visualize your characters.

Their growth. What we call “the hero's journey” would be incomplete without the infamous protagonist’s evolution or the learning experiences they will go through. In the treatment, we expect to see the different stages of your character’s growth–even if the hero does not change much or if they go full circle and come back to how they always were at the beginning of the film.

Their relationship with others. A film's character rarely walks alone. At the center of their ecosystem, the character interacts and clashes with others–be it with friends or enemies. In the treatment, it is, therefore, crucial to explain who is who and describe the hero’s friend or enemy. What roles do the secondary characters play? How will the characters' relationships evolve? The treatment must answer these questions.

5) Manual of style: How to write a treatment? What tone to use? How to describe the atmosphere?

I could not emphasize this enough: even an interesting story with gripping content can be discarded if it is badly written. As a case in point, I have read my fair share of badly written treatments and I dismissed them all–no matter how good the concept was!

Since it is his job, a screenwriter must master the art of writing a treatment.

🖊But, what does writing a good treatment entail?

It requires for you to describe the film in the same way you would write a novel: with the innate drive to captivate the reader.

BUT that said, and this might set one’s teeth on edge here, I do not believe you can teach someone to write well.

The knowledge associated with good writing comes from years of reading, plus even more years of practice, and admittedly, an inclination to this art form. In other words, there is no training course for writing: either the screenwriter can write, or they cannot.

All these considered, although miracles are rare, you can, however, do some damage control by following these tips:

✅ Write sentences that flow smoothly,

✅ Stay visual,

✅ Manage the pace: don't rush, but don't be too slow either,

✅ Stimulate emotions

✅ Make your text dynamic, namely by including a couple of lines of dialogue (more on this later)

⛔️ Avoid sentences that are too long,

⛔️ Avoid repetitions in the same sentence or paragraph,

⛔️ Be literary, but don't overdo it,

⛔️Avoid sounding too harsh or crude.

Finally, to give your treatment life and soul, let the film’s genre inspire you. If you are writing a romantic comedy, you should write with humor and romance. If you are writing a thriller, give them a taste of suspense. Whatever the movie's genre, you must always keep in mind this rule of thumb: "Captivate us! Captivate us! Captivate us!"

5) Less is more: What can you leave out in the treatment?

One of the major mistakes people make when writing their treatment is to want to explain everything and they go on mindlessly saying it all. This is a bad habit if we refer to the common saying “Less is More”. To ensure the reader’s experience regarding your treatment is as pleasant as possible, you should select the key elements of your story and forgo the less essential ones.

For example, there is no need to talk about every single character or describe every single micro-twist, for instance, those non-fundamental items to the main or subplot’s development.

6) In summary the worst screenplays I have read:

Were badly written,

Lacked clarity,

Had an inconsistent story, and

Were simply not appealing.

Therefore, it is up to you and your writer to make sure your material is none of these things!

⚠️The article is also available in PDF format. To start with download, click here.

Letter of intent.

1) The statement of intent: definition and purpose:

As its name suggests, the statement of intent indicates the writer’s and director’s intention. It serves as a springboard to explain the genesis of the story and the writer's vision and it helps convince us of the project's relevance.

It is a tool you need to master that should not be more than two or three pages long.

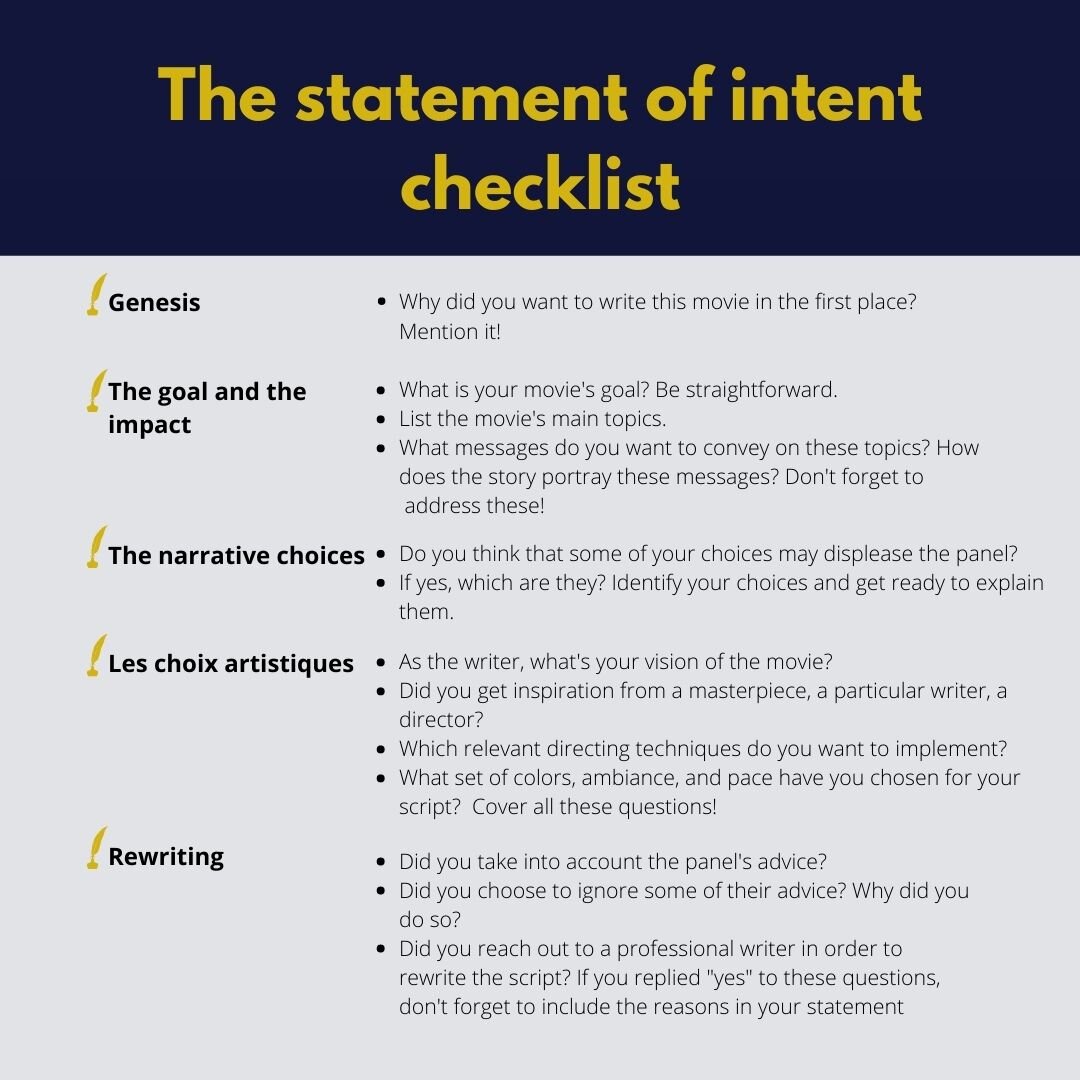

2) What to include in a statement of intent?

Although the statement of intent’s content may vary from one project to another, here are key points I recommend to any writer that I work with to include:

a)The genesis.

I always urge writers to start their statement of intent by introducing the project’s genesis–explaining why it exists, what made the author want to write it, the purpose, or rationale if you will.

Did the project originate from a particular topic? Is it from a desire to speak about a well-known or unknown character? Or, a wish to represent historical events? Is it an adaptation? (if so, why this adaption? This is the part where these questions are answered.

b)The project's purpose and impact.

The statement of intent is also where you include the project’s purpose–its ultimate goal. Although this may seem odd if the project has no purpose then why should it see the light of day?

In my opinion, a work’s purpose is bound by these two concepts:

the concept of entertainment–which every film has in common, and

the concept of a message (unique to each writer) inextricably linked to the story’s topics.

→ Is this project made to entertain (and solely to entertain)? What are the important themes in the screenplay and why? Does the film carry a message the writer wishes to express? If so, what is that message? These are some of the answers we would expect you to include in your statement.

c) Prove that the project resonates with the current times.

I recommend the writer to use their statement to demonstrate how their project is anchored in today’s reality. Even if the story takes place in the older days, its topics and problems need to resonate with those in today’s society. Otherwise, it will lose the public’s interest.

3) What to add to a statement of intent in case of a rewrite?

In the case of a second application for funding for the same project (which is a common occurrence), the statement of intent’s content will be slightly modified. Here's what you should include:

a) Remind the panel of the project’s genesis and goal.

In order to refresh the panel's memory, do not hesitate to remind them of the project’s genesis or put forward the writer’s goal.

b) Mention the adjustments.

To send a film back to a panel without making any of the requested adjustments to the application would amount to shooting oneself in the foot. The central goal of the new statement is to demonstrate that some suggestions were taken into consideration and to justify the narrative choices in cases when the writer has opted not to follow some of the recommendations.

c) Talk about the co-writer or script-doctor.

If you called in a co-writer or script-doctor to help your writer rework the project, disclose it. It is proof that you take this project seriously and want it to move forward, and then explain the specific ways in which their interventions have helped the story progress.

The Pitch.

Most commission panels may ask the writers and producers to supply a 3-sentence summary of the project: This is what we call the written pitch.

In my opinion, writing a pitch is one of the hardest tasks there is. I find it even more complex than writing an entire screenplay, treatment, or statement of intent.

Think about it, summarizing 120 pages in only 3 sentences is far from easy. Which words or phrasing will convince them?

That is a tricky question I will attempt to answer here. But first, let’s begin with the definition of a pitch.

1) What is a pitch? What is it for?

As mentioned, the pitch is an extremely condensed summary of the film. The pitch is the hook that will make the viewers want to see the film and the readers want to read the script.

2) Techniques to write a great pitch:

Although writing a pitch is an onerous task, these tips may come in handy:

Identify the concept. To succeed in writing a pitch, it is useful to start by identifying the story's core element–also known as the concept or premise. What is the film’s core that defines its existence? To define the story's essence, I encourage you to write a sentence starting with: “This is the story of…”. Once you are done, delete the beginning of that same sentence (i.e. “This is the story of”). This is when the story’s core should reveal itself. You can rewrite the sentence many times over until you get the ideal outcome.

A caution for producers is that if the writer is incapable of articulating their projects, it probably means they lack professionalism and could be a warning for the future. Be watchful.

Beyond just the film’s concept, other tips to keep in mind in writing an efficient pitch, are:

Utilize the most important pivots of the plot. The writer may choose to include some of the most important parts of the twist in the predicaments the hero will need to face.

Add suspense. Nothing is stopping you from adding some suspense to make the pitch as appealing as possible.

Start with the setup. The writer may also want to start off by describing the setup before adding a triggering event in order to, once again, build suspense.

On the internet, you can find a multitude of websites that index film pitches. I would encourage you to look into them to better understand what is expected of the writer.

Here is one:

Film Daily TV: https://www.filmdaily.tv/logline/top-box-office-logline-examples

The dialogue.

It is not rare for television or film funding programs to ask that you add a good measure of dialogue pages to your application file. Consequently, you will want to do more than simply writing them on the back of a napkin and sending them along–as if a hurried afterthought. It's a must to choose brilliant dialogues and scenes.

To write good dialogue, you obviously need talent (decent dialogue writers are hard to find); but, practice helps a lot as well.

Firstly, let’s explore what defines great dialogue.

1) What makes dialogue good?

Dialogue that is worth more than silence. This is a dialogue that exists without disturbing silence and emotion. I often say that silence or images are worth more than words. Take that into consideration for your scenes.

Dialogue that is unique to each character. Each character must express themselves differently because each is unique; and, that must come across clearly in their phrasing. Maybe your characters talk in long sentences or short ones, maybe they use swear words, maybe they are extremely polite, maybe they have an accent, maybe they do not, maybe they change their tone depending on whom they are talking to. No matter how the characters express themselves, it is the writer's job to define tiny details, such as these, and this process must be done during the characterization phase.

Fluid dialogue. The characters must have natural and interactive conversations. For that, you need dialogue and words that people in the real world would use. The characters must express their truths at all times. Do not simply take my word for it, this is all from Stephen King in his book On Writing.

2) Selecting the dialogue pages.

Selecting which dialogue pages to add to your application essentially means selecting the best segments of your film. But which ones?

You should choose the highlights of your project. This could be anything from a scene when most action takes place, the end of an act, a climax, or a very moving scene to a funny, rich, or suspenseful one. It can also be the hero’s revelation moment. Whichever scene you choose, it must enable the readers to picture the characters and make them want to read your screenplay.

⚠️ Want the article in PDF file? All you need to do is click here.

Conclusion.

I truly hope you find this guide valuable and helpful in your application files. I would love to know: Are you working on anything at the moment, if so what is it? Any feature film or short-film projects? How are you getting on with writing your screenplays and statements of intent? Do let me know in the comments.